Review: Half of a Yellow Sun, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Those of a certain age will recall the Biafran war of independence in the 1960s when images of starving children filled the pages of newspapers and Sunday colour supplements. It was a horrific war in West Africa’s Nigeria when hundreds of thousands died not from bullets or missiles but starved to death as the Nigerian army slowly strangled the fledgling state to surrender. The sickening starvation witnessed by Olanna in a camp where children were ‘naked, their taut globes that were their bellies,’ and where a dead mother with her baby clinging to her is dragged away by her hands and ankles may be fiction but it is also true as the media in the late 60s covered the horrors of starvation.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s depiction of the media in the form of overweight American journalists in her novel Half of a Yellow Sun depict the only representatives of the fourth estate as shallow racist bigots who are interested in peripheral stories such as the death of one white man rather than the tragedy of war. It was the one point in the novel where the truth was partly fictionalised as there was extensive and empathetic coverage by the international media at the time with numerous eye witness accounts from Biafra – especially by European reporters.

That grouch aside Half of a Yellow Sun is an epic story of several characters who represent different aspects of those caught up in the war. Ugwu is the young servant who matures into a responsible adult and is the backbone of the narrative. Olanna and Kainene represent different sides of twin sisters – social minded Olanna the lover of Biafran Odenigbo a Professor of Mathematics – and business minded Kainene the lover of Richard Churchill an Englishman trying to find himself in Africa. All are decent people who are all affected in different ways by the war with none escaping completely the horrors.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie successfully blends her fiction with fact giving a vivid account of the war through the lives of the characters. Much of the time the war is in the background and creeps up on the protagonists while they are distracted by their private lives. But it all starts before the war when only hints of what is to come are slipped into their lives – but as war approaches Richard muses, “it was as if the people of this city with the tall whistling pins wanted to grab all they could before the war robbed them of choices.”

A striking aspect is the way the privileged lives of Olanna and Odenigbo and their social circle in the opening chapters are descripted. Swimming pools, tennis clubs and drinks at the club – so in contrast to the lives of their servants like Ugwu and his circle that included his ailing mother and various relatives. Olanna is concerned about class and social status and worries about moving house that: “She hoped Professor Achara had found them accommodation close to other university people so that Baby would have the right kind of children to play with.” Such a divide between rich and poor from the jet setting academics and Government officials to the lives of most Nigerians – the Igbo, Hausa-Fulani or Yoruba who are encouraged to set upon each other by cynical politicians and members of the military – is stark.

Essentially much of Nigeria (especially in the north) is dominated by the ethic Hausa, Fulani and Yoruba who largely are Muslims and have different traditions and languages to the Igbos who live mainly in the south and east of the country and by tradition are largely Christian. It’s a story of ethnic cleansing and genocide prompted by vested interests’ ambitious groups in the army and political groups after power and wealth. And also once the war starts by the likes of the former colonial masters of the British Government, but also America, Russia and petrochemical firms who sided with Nigeria fearing the loss of the oil rich lands of the south to the Biafrans.

It is a very readable and gripping novel and down to earth with its descriptions of the characters’ inner thoughts, their sex lives, their habits and what food they like. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie also gives much insight into the languages of the country and how inflections, accents and status allow people to judge others – a bit like we do in England.

Half of a Yellow Sun flips back and forth in time to give a sense of the impending doom and to illustrate the post-colonial world where the inheritors of Nigeria seemingly mimic their former British rulers’ lifestyles. From the news of the first miliary coup led by Igbo army officers in 1967 to the army uniforms complete with the Biafran symbol of half a yellow sun on their tunics to the bedraggled and dirty conscripts as the Nigerian forces close in it’s a story well told and essential reading for anyone wishing to understand the country post colonialism in general.

One reviewer spoke of a long-forgotten war – but Biafra hasn’t gone away – Biafra continues to lobby for independence to this day.

Harry Mottram

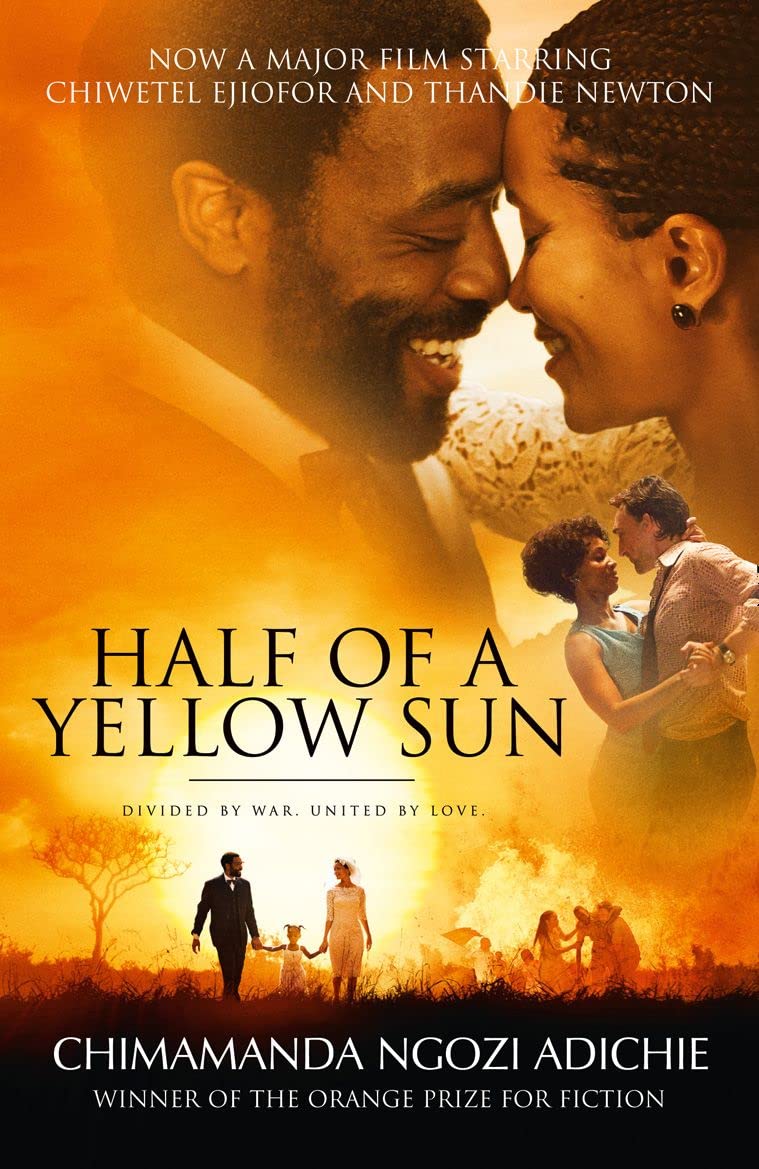

Half of a Yellow Sun was adapted into a film in 2013 directed by Biyi Bandele as an Anglo Nigeria production.

Half of a Yellow Sun was chosen by the Four Seasons Axbridge Book Club to discuss on February 27, 2023.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie gave the first of four 2022 Reith Lectures on freedom, looking at what freedom of speech means for the BBC in 2022. See https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001fmtz

Rapscallion Magazine is an online publication edited by Harry Mottram

Harry is a freelance journalist. Follow him on Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube etc

Email:harryfmottram@gmail.com

Website:www.harrymottram.co.uk

Mobile: 07789 864769

You must be logged in to post a comment.